Susan Derges and David Chandler, Director of Photoworks, first worked together on the exhibition Between Sun and Earth at The Photographers' Gallery, London in 1992. Since then they have maintained a regular dialogue both through specific projects and more generally through a sharing of ideas. In this interview, a part of which first appeared in Next Level magazine in 2003, they discuss some of the ongoing themes and more recent developments of Derges' work.

David Chandler: It has always seemed to me that the body is a constant presence in your work, not just in the sense that your working processes have often had a performative aspect, but also in the way you embrace systems of growth and decay, of flow and interchange - as you have said, you can see the workings of the imagination as flow forms from a river. And seeing nature in terms of the body also suggests the continual sense of both micro and macro scales in your work. Perhaps you could say a little about the relationship between the interior and exterior in your work.

Susan Derges: Well, it might be interesting to begin here with earlier series such as River Taw and Under The Moon, where the works reflect a human scale, where the body is directly referenced in the long, thin, vertical format of the prints. The format deliberately counteracts any sense of looking through an aperture but rather suggests a more direct relationship, or experience of immersion in the image. In the making of Under The Moon there was a very physical experience of working with the water and branches in the darkroom. Although how the works were made is not particularly important for anyone to know, method always resonates with the ideas and it might be helpful to stress that I was not going out into the landscape to make prints in the river at night, as with the River Taw photograms, but actually brought photographs I had made of the moon into the darkroom, combining them with direct prints of water and branches that were vibrated by sound - all of which sounds rather strange but it was an attempt to make visible the relationships between the moon, water, living matter and by implication the observer. They were put together much in the way that the unconscious might construct dreamt or imagined imagery, and it hasn't surprised me that people say they are reminded of dreams, fairytales and early memories on first looking at the prints. In the process of making I became fairly obsessed with the changing cycles of the moon and particular places in the landscape that I was visiting while thinking about the work and it became very easy to move between a kind of internal landscape of imagined and metaphorical imagery and the external counterpart. Neither seemed more real than the other, they seemed to inform each other in a way that was more fluid than before. The macro cycles of the moon and external nature became identified with the changing states of the microcosm of the self - hopefully not as purely autobiographical records but of a more archetypal or universal nature.

DC: This sense of internalisation, looking at the space both real and imagined within the body, really began with the Natural Magic light boxes that were made during your residency at the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford. The internal space here was that of the mind, and more specifically the 'creative' approach to science that embraced alchemical processes. Could you say something of the context and making of Natural Magic, and also its impact on your subsequent work?

SD: When I arrived at the Museum they were still involved in a major refurbishment of the building - so the collection was packed away but they had just unearthed from beneath the basement some very early chemical vessels as well as human and animal remains that indicated alchemical experiments as well as anatomical dissections had been carried out there in the early days of Elias Ashmole. The idea of this dark smokey, basement laboratory, sealed off from the rest of the collection of astrolabes, telescopes, surveillance and measuring instruments, seemed analogous to the way we view internal space - and how the unconscious is seen as chaotic, hidden and kept separate from everyday conscious mental life. I was interested in how early science actually allowed for unconscious processes to merge with the material world - how observation was a creative psychological process as much as one of quantifying objects. In early chemistry, because of the difficulty of making accurate measurements, vessels and experiments operated almost like containers or screens for projected unconscious imaginative material. I found the excitement and wonderment and blurring of the boundaries between internal and external life very rich and wanted to re-animate some of the magic the natural philosophers would have experienced in experiments like the distilling of aquae vitae. In relation to subsequent work, the distillation experiment certainly informed my ideas for the Eden series and how the hydrological cycle in the natural world ñ just like the processes of energy, heat, evaporation, condensation, precipitation and collection within the alembic ñ could also be seen as a metaphorical narrative of internal or psychological transformation.

DC: Alchemy seems to symbolise a point of interface between our intellectual curiosity - that human drive for knowledge cast out into something boundless and unknowable: nature, the universe - and some other impulse that is more to do with how we need to exert a form of control over that boundless complexity, the need to transform as a product of understanding. There seems to be a tension here, one that alchemy expresses, between an imaginative grasp of nature and something more to do with base materiality. It is something that also alludes to the division or tension that exists between what you have often referred to as the holistic and mechanistic views of the world. Does the creative freedom, or the magic of alchemy also embody a sense of turmoil for you? It's something that seems to be there as an undercurrent in your work, particularly the more recent series.

SD: I think what it holds for me is the sense that the quest for truth or knowledge must involve the mind and body that that seeks it. That seems to be a point of tension between holistic and mechanistic views: one is inclusive and the other does not take into account any form of subjective or imaginative involvement in the processes of observation and exploration. I think when you start to look at the implications of the observer's relationship to the observed and the ways in which mind projects and imputes meaning and substance onto what we think we see, there is a kind of turmoil or shifting ground that is very uncomfortable. In the recent work I was much clearer about wanting to express that ambiguous visual sense of things not being quite what they seem. In the River Taw and Eden series the focus was more on the ephemeral, transient nature of the world we think of as solid and predetermined. In relation to the recent work, the unease or turmoil of being visually located in the projection instigates a process of exploration that as you say connects with the need to transform, perhaps in order to see more clearly.

DC: The Eden series took you back outside ñ literally and metaphorically into the spaces and processes of the external world. Given this work came from a commission, within which certain constraints, as well as opportunities, were imposed and offered, how did this work sit with the development of your ideas. In one sense the project seems a bit of a one-off, where you are taking on for the first time architectural issues, including thinking through how the viewing of your work might blend into the experience of architectural space.

SD: It was very much a one-off and in a way took me back to earlier working methods and subject matter and away from what I was developing in the studio, although some new ideas came out of it that I've used in the recent work. The Education Center at Eden was designed around the metaphor and growth structures of the forest canopy and I was invited to consider working with some of the glass in the building. It seemed almost obvious that the water cycle in relation to the canopy was a way of looking at a circular terrace of large glass panels in the roof of the building. The distillation sequence from Natural Magic provided a kind of circular narrative of continual change and transformation that I used to make photograms of cloud, rain, streams, rivers, shorelines, evaporation, freezing, condensation and cloud. The photograms were scanned and digitally printed on to the laminate that fuses two sheets of architectural glass together so that in effect they became large glass transparencies, surrounding the solar terrace. Working on an architectural scale, collaborating with the architects and designers on the spaces and detailing of the commission was a great experience but I had not anticipated the extent of loss of control over how the building would ultimately be occupied and used and this felt very uncomfortable.

DC: The more recent works have been aligned again with more internal narratives and yet in many ways their construction employs elements more generally associated with traditional landscape. But the 'view' we have creates a profound disorientation, we are not sure whether we are looking up into space or down at a reflection, into a mirror - neither seems to hold true. The suggestion of 'shallow' space found in the River Taw work and then again, though not so straightforwardly, in the Eden series flat fields of activity spread across the picture plane has become an indeterminate space that draws the eye in, either through an aperture-like opening or over a foreground 'horizon'. Formally this is a profound shift, so that instead of scanning the works, reading across them, our attention is focused and lead through a narrative of depth. For me, that is also the replacing of a restive accent in the work a form of meditative looking ñ towards something more forceful and dynamic, pulling the viewer into a kind of vortex. Would you agree with that, and if so how does this formal shift connect with the concerns of the work?

SD: Yes I agree, and it is quite a change in approach. In the River Taw and Eden prints, although the metaphor of being submerged was implicit in the way of making the prints, it was actually a very shallow space or depth of field and as you say the emphasis was on movement across the surface of the paper, flow-forms unfolding along the length of the images, re-animated as you scanned them. In the cloud series this liquid movement is stilled and becomes mirror like. It is a much more ambiguous space, more disorientating, as one thinks one is looking up out of an enclosed world into deep space and yet it is not quite right. It might be a mirror reflection, or one might be submerged beneath the surface of a pond or a well looking out, up at the sky. I wanted to visualise the idea of a threshold where one would be on the edge of two interconnected worlds: one, an internal, imaginative or contemplative space and the other, an external, dynamic, magical world of nature. I am interested in how the two interact, how they project on to or into each other and destabilise the ideas we normally have of ourselves and the surrounding environment.

DC: "But all things are composed here

Like Nature, orderly and near:

In which we the Dimensions find

Of that more sober Age and Mind,

When larger sized Men did stoop

To enter at a narrow loop;

As practising, in doors so strait,

To strain themselves through Heavens Gate."

These and other lines from Andrew Marvell's poem Upon Appleton House, to my Lord Fairfax seem to have a direct bearing on the new work. You have said that the poem, once described as an 'alchemical narrative', has become an important reference point for you. Could you elaborate a little on this?

SD: Yes, after I finished the cloud series I was looking for a way to make sense of some of the things that had come out the unfolding sequence of images and picked up Lyndy Abrahams book about Marvell and Alchemy. To be honest I was also looking for help with titles, but was amazed at some of the connections between the authors alchemical interpretation of the poem Upon Appleton House and the imagery in the new work. Very briefly, the poem is a narrative or rather a circular meditation on an alchemical process of metamorphosis that is represented by the house at Appleton, the characters and the whole of the natural environment which operate as metaphors for processes of psychological or spiritual transformation. The symbols that I found shed light on my own imagery were concerned with the idea of the flux and chaos of the river becoming stilled into a crystal mirror, "where there is doubt as to which is reality and which is the reflection or shadow". This process of stilling or calming is instigated in the poem by a mythical bird - the Halcyon - that brings this crystalline mirror-like quality to a distorted, chaotic, state. "Where all things gaze themselves and doubt, If they be in it or without, And for his shade, which therein shines, Narcissus like the sun too pines". The sun pining for it's shadow the moon, the union of Sol and Luna in the mirror are representations of the merging of subject and object and the bringing of consciousness into form. In the poem there is a point where all of nature is described as dyed blue, which in alchemical terms is the quintessential azure dye that is said to represent the conferral of new form onto formless consciousness. The Halcyon is connected to this process of dyeing in the poem "The stilling magic of the Halcyon's saphire mist" and the Halcyon is also closely associated with the 'child' of the union of day and night, who instigates a process of transformation and renewal where all of nature is vitrified or turned into glass, mirroring itself back to its source

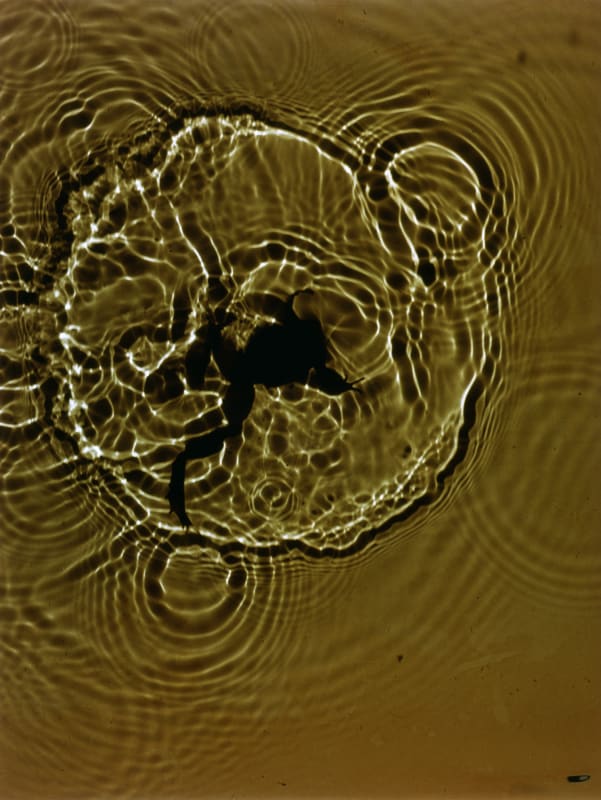

DC: This brings me to one of your most recent works where, very unusually for your work, a figure appears. It is the figure of a child you have alluded to one associated in alchemic terms with 'the starry sphere' and perhaps more pointedly suggesting a harmonising presence. The child is traditionally a sign of purity and innocence, but also suggests a sense of human potential continually renewed, reborn. Do you feel that the inclusion of a human figure, and with it the more literal connection between nature and us, marks another turning point for you?

SD: The child image has become for me connected to the first image of sycamore twigs in bud. They seem to communicate a vivid sense of potential new growth surrounding the incubating, nest-like space that encircles the sky, or out of which one would see the sky. The child, as you say, communicates a feeling of human potential renewed or reborn. The philosophical child that appears in Marvell's poem is associated with the stars in the alchemical sense that she/he is nourished by or born out of the stars which I suppose we are too ñ and in that way we become the child and there is a connection made with our source. Although the connection between ourselves and nature has been around as an idea in most of my work, this feels like a very different perspective, where, rather than being the implied participant of the earlier work, we are now literally creating the 'nature' we think we observe, as well as being created by it.

Susan Derges and David Chandler, Director of Photoworks, first worked together on the exhibition Between Sun and Earth at The Photographers' Gallery, London in 1992. Since then they have maintained a regular dialogue both through specific projects and more generally through a sharing of ideas. In this interview, a part of which first appeared in Next Level magazine in 2003, they discuss some of the ongoing themes and more recent developments of Derges' work.

David Chandler: It has always seemed to me that the body is a constant presence in your work, not just in the sense that your working processes have often had a performative aspect, but also in the way you embrace systems of growth and decay, of flow and interchange - as you have said, you can see the workings of the imagination as flow forms from a river. And seeing nature in terms of the body also suggests the continual sense of both micro and macro scales in your work. Perhaps you could say a little about the relationship between the interior and exterior in your work.

Susan Derges: Well, it might be interesting to begin here with earlier series such as River Taw and Under The Moon, where the works reflect a human scale, where the body is directly referenced in the long, thin, vertical format of the prints. The format deliberately counteracts any sense of looking through an aperture but rather suggests a more direct relationship, or experience of immersion in the image. In the making of Under The Moon there was a very physical experience of working with the water and branches in the darkroom. Although how the works were made is not particularly important for anyone to know, method always resonates with the ideas and it might be helpful to stress that I was not going out into the landscape to make prints in the river at night, as with the River Taw photograms, but actually brought photographs I had made of the moon into the darkroom, combining them with direct prints of water and branches that were vibrated by sound - all of which sounds rather strange but it was an attempt to make visible the relationships between the moon, water, living matter and by implication the observer. They were put together much in the way that the unconscious might construct dreamt or imagined imagery, and it hasn't surprised me that people say they are reminded of dreams, fairytales and early memories on first looking at the prints. In the process of making I became fairly obsessed with the changing cycles of the moon and particular places in the landscape that I was visiting while thinking about the work and it became very easy to move between a kind of internal landscape of imagined and metaphorical imagery and the external counterpart. Neither seemed more real than the other, they seemed to inform each other in a way that was more fluid than before. The macro cycles of the moon and external nature became identified with the changing states of the microcosm of the self - hopefully not as purely autobiographical records but of a more archetypal or universal nature.

DC: This sense of internalisation, looking at the space both real and imagined within the body, really began with the Natural Magic light boxes that were made during your residency at the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford. The internal space here was that of the mind, and more specifically the 'creative' approach to science that embraced alchemical processes. Could you say something of the context and making of Natural Magic, and also its impact on your subsequent work?

SD: When I arrived at the Museum they were still involved in a major refurbishment of the building - so the collection was packed away but they had just unearthed from beneath the basement some very early chemical vessels as well as human and animal remains that indicated alchemical experiments as well as anatomical dissections had been carried out there in the early days of Elias Ashmole. The idea of this dark smokey, basement laboratory, sealed off from the rest of the collection of astrolabes, telescopes, surveillance and measuring instruments, seemed analogous to the way we view internal space - and how the unconscious is seen as chaotic, hidden and kept separate from everyday conscious mental life. I was interested in how early science actually allowed for unconscious processes to merge with the material world - how observation was a creative psychological process as much as one of quantifying objects. In early chemistry, because of the difficulty of making accurate measurements, vessels and experiments operated almost like containers or screens for projected unconscious imaginative material. I found the excitement and wonderment and blurring of the boundaries between internal and external life very rich and wanted to re-animate some of the magic the natural philosophers would have experienced in experiments like the distilling of aquae vitae. In relation to subsequent work, the distillation experiment certainly informed my ideas for the Eden series and how the hydrological cycle in the natural world ñ just like the processes of energy, heat, evaporation, condensation, precipitation and collection within the alembic ñ could also be seen as a metaphorical narrative of internal or psychological transformation.

DC: Alchemy seems to symbolise a point of interface between our intellectual curiosity - that human drive for knowledge cast out into something boundless and unknowable: nature, the universe - and some other impulse that is more to do with how we need to exert a form of control over that boundless complexity, the need to transform as a product of understanding. There seems to be a tension here, one that alchemy expresses, between an imaginative grasp of nature and something more to do with base materiality. It is something that also alludes to the division or tension that exists between what you have often referred to as the holistic and mechanistic views of the world. Does the creative freedom, or the magic of alchemy also embody a sense of turmoil for you? It's something that seems to be there as an undercurrent in your work, particularly the more recent series.

SD: I think what it holds for me is the sense that the quest for truth or knowledge must involve the mind and body that that seeks it. That seems to be a point of tension between holistic and mechanistic views: one is inclusive and the other does not take into account any form of subjective or imaginative involvement in the processes of observation and exploration. I think when you start to look at the implications of the observer's relationship to the observed and the ways in which mind projects and imputes meaning and substance onto what we think we see, there is a kind of turmoil or shifting ground that is very uncomfortable. In the recent work I was much clearer about wanting to express that ambiguous visual sense of things not being quite what they seem. In the River Taw and Eden series the focus was more on the ephemeral, transient nature of the world we think of as solid and predetermined. In relation to the recent work, the unease or turmoil of being visually located in the projection instigates a process of exploration that as you say connects with the need to transform, perhaps in order to see more clearly.

DC: The Eden series took you back outside ñ literally and metaphorically into the spaces and processes of the external world. Given this work came from a commission, within which certain constraints, as well as opportunities, were imposed and offered, how did this work sit with the development of your ideas. In one sense the project seems a bit of a one-off, where you are taking on for the first time architectural issues, including thinking through how the viewing of your work might blend into the experience of architectural space.

SD: It was very much a one-off and in a way took me back to earlier working methods and subject matter and away from what I was developing in the studio, although some new ideas came out of it that I've used in the recent work. The Education Center at Eden was designed around the metaphor and growth structures of the forest canopy and I was invited to consider working with some of the glass in the building. It seemed almost obvious that the water cycle in relation to the canopy was a way of looking at a circular terrace of large glass panels in the roof of the building. The distillation sequence from Natural Magic provided a kind of circular narrative of continual change and transformation that I used to make photograms of cloud, rain, streams, rivers, shorelines, evaporation, freezing, condensation and cloud. The photograms were scanned and digitally printed on to the laminate that fuses two sheets of architectural glass together so that in effect they became large glass transparencies, surrounding the solar terrace. Working on an architectural scale, collaborating with the architects and designers on the spaces and detailing of the commission was a great experience but I had not anticipated the extent of loss of control over how the building would ultimately be occupied and used and this felt very uncomfortable.

DC: The more recent works have been aligned again with more internal narratives and yet in many ways their construction employs elements more generally associated with traditional landscape. But the 'view' we have creates a profound disorientation, we are not sure whether we are looking up into space or down at a reflection, into a mirror - neither seems to hold true. The suggestion of 'shallow' space found in the River Taw work and then again, though not so straightforwardly, in the Eden series flat fields of activity spread across the picture plane has become an indeterminate space that draws the eye in, either through an aperture-like opening or over a foreground 'horizon'. Formally this is a profound shift, so that instead of scanning the works, reading across them, our attention is focused and lead through a narrative of depth. For me, that is also the replacing of a restive accent in the work a form of meditative looking ñ towards something more forceful and dynamic, pulling the viewer into a kind of vortex. Would you agree with that, and if so how does this formal shift connect with the concerns of the work?

SD: Yes I agree, and it is quite a change in approach. In the River Taw and Eden prints, although the metaphor of being submerged was implicit in the way of making the prints, it was actually a very shallow space or depth of field and as you say the emphasis was on movement across the surface of the paper, flow-forms unfolding along the length of the images, re-animated as you scanned them. In the cloud series this liquid movement is stilled and becomes mirror like. It is a much more ambiguous space, more disorientating, as one thinks one is looking up out of an enclosed world into deep space and yet it is not quite right. It might be a mirror reflection, or one might be submerged beneath the surface of a pond or a well looking out, up at the sky. I wanted to visualise the idea of a threshold where one would be on the edge of two interconnected worlds: one, an internal, imaginative or contemplative space and the other, an external, dynamic, magical world of nature. I am interested in how the two interact, how they project on to or into each other and destabilise the ideas we normally have of ourselves and the surrounding environment.

DC: "But all things are composed here

Like Nature, orderly and near:

In which we the Dimensions find

Of that more sober Age and Mind,

When larger sized Men did stoop

To enter at a narrow loop;

As practising, in doors so strait,

To strain themselves through Heavens Gate."

These and other lines from Andrew Marvell's poem Upon Appleton House, to my Lord Fairfax seem to have a direct bearing on the new work. You have said that the poem, once described as an 'alchemical narrative', has become an important reference point for you. Could you elaborate a little on this?

SD: Yes, after I finished the cloud series I was looking for a way to make sense of some of the things that had come out the unfolding sequence of images and picked up Lyndy Abrahams book about Marvell and Alchemy. To be honest I was also looking for help with titles, but was amazed at some of the connections between the authors alchemical interpretation of the poem Upon Appleton House and the imagery in the new work. Very briefly, the poem is a narrative or rather a circular meditation on an alchemical process of metamorphosis that is represented by the house at Appleton, the characters and the whole of the natural environment which operate as metaphors for processes of psychological or spiritual transformation. The symbols that I found shed light on my own imagery were concerned with the idea of the flux and chaos of the river becoming stilled into a crystal mirror, "where there is doubt as to which is reality and which is the reflection or shadow". This process of stilling or calming is instigated in the poem by a mythical bird - the Halcyon - that brings this crystalline mirror-like quality to a distorted, chaotic, state. "Where all things gaze themselves and doubt, If they be in it or without, And for his shade, which therein shines, Narcissus like the sun too pines". The sun pining for it's shadow the moon, the union of Sol and Luna in the mirror are representations of the merging of subject and object and the bringing of consciousness into form. In the poem there is a point where all of nature is described as dyed blue, which in alchemical terms is the quintessential azure dye that is said to represent the conferral of new form onto formless consciousness. The Halcyon is connected to this process of dyeing in the poem "The stilling magic of the Halcyon's saphire mist" and the Halcyon is also closely associated with the 'child' of the union of day and night, who instigates a process of transformation and renewal where all of nature is vitrified or turned into glass, mirroring itself back to its source

DC: This brings me to one of your most recent works where, very unusually for your work, a figure appears. It is the figure of a child you have alluded to one associated in alchemic terms with 'the starry sphere' and perhaps more pointedly suggesting a harmonising presence. The child is traditionally a sign of purity and innocence, but also suggests a sense of human potential continually renewed, reborn. Do you feel that the inclusion of a human figure, and with it the more literal connection between nature and us, marks another turning point for you?

SD: The child image has become for me connected to the first image of sycamore twigs in bud. They seem to communicate a vivid sense of potential new growth surrounding the incubating, nest-like space that encircles the sky, or out of which one would see the sky. The child, as you say, communicates a feeling of human potential renewed or reborn. The philosophical child that appears in Marvell's poem is associated with the stars in the alchemical sense that she/he is nourished by or born out of the stars which I suppose we are too ñ and in that way we become the child and there is a connection made with our source. Although the connection between ourselves and nature has been around as an idea in most of my work, this feels like a very different perspective, where, rather than being the implied participant of the earlier work, we are now literally creating the 'nature' we think we observe, as well as being created by it.